| ALFRED KORZYBSKI Printed by the Graphic Press, 39 W. 8th St., N. Y. C. Photographs by the Fernand Studios, N. Y. C. Presented in abstract before the International Mathematical Congress, August, 1924, Toronto, Canada |

| (This paper is a summary of a larger work on Human Engineering soon to be published.) |

ALL HUMAN knowledge is conditioned and limited, at present, by the properties of light and human symbolism. The solution of all human problems depends upon inquiries into these two conditions and limitations.

Einstein's theory is a fundamental inquiry and application of the known properties of light; theirrefutable minimum of his theory results in an entirely new world conception, as beautiful and cheerful as the old ones were gloomy and despairing.

The minimum of our inquiry into the structure of human knowledge and symbolism is also irrefutable, and this beginning, imperfect as it may be, has already enormous beneficial consequences.

Einstein's theory was the application of modern scientific methods to the universe, man excluded. The present inquiry includes man in the field of modern science. As a result, both theories meet on a common ground.

The theory presented here is broader than Einstein's. It may be proved that the whole of the theory of relativity can be deduced from the application of correct symbolism to facts; so that the general theory of Time-binding includes the general theory of relativity as a particular case.

For a full understanding this essay should be read twice, at least, because the beginning presupposes the end, and vice versa. This theory is built upon the minimum of the best ascertained scientific facts of 1924. Its scientific soundness has to be judged on theoretical grounds (1924). Its working cannot be judged by arguments, only by application. Fortunately, it works with the reader who has understood it. If it does not work, the reader has not understood.

For a full understanding this essay should be read twice, at least, because the beginning presupposes the end, and vice versa. This theory is built upon the minimum of the best ascertained scientific facts of 1924. Its scientific soundness has to be judged on theoretical grounds (1924). Its working cannot be judged by arguments, only by application. Fortunately, it works with the reader who has understood it. If it does not work, the reader has not understood.

We cannot argue as to whether the sun is shining, we must go and see. In the case here presented, arguments alone are also not legitimate.

Statements containing variables are called "propositional functions"; they are neither true nor false. When values are assigned to such variables the expressions become propositions, which are either true or false. (Russell.)

Many words are names for stages of processes and are therefore variables, as for instance, "civilization", "science", "humanity", "mathematics", etc., etc. To generate a proposition with such words, we must assign to them a value through the use of co-ordinates. For our purpose, it will be sufficient to use only the time-co-ordinate, which will be indicated by the year in parenthesis, such as "science (1924)."

Obviously "science (1924)" is a different affair from "science (1500)," or "science (300 B. C.)." In the field of this investigation the term "science" means, for the majority, "science (300 B. C.)," or, at best, "science (1800 A. D.)." For such readers, this inquiry will be incomprehensible.

Most, not all, of the details of this general theory are vaguely known; it seems that the main novelty consists in the building up of an autonomous system. Such systems, if scientific, are useful; they economize thought and bring to light truths as well as fallacies. In a deeper sense fallacies, if scientific, are often as useful as truths, because they open new and unexpected fields for inquiry. Probably no system is true, although this statement does not include mathematics which does not claim to be true but to be correct.

The scientific revolution started with Geometry, and, in a deeper sense, it is carried on by Geometry. Until Gauss, Lobachevski, Bolyai, Riemann, etc., the Euclidean Geometry, beingunique, was theologically believed to be the geometry of the space. The moment a second geometry was produced, "just as good," self-consistent, yet contradictory to the old one, the geometry became ageometry. None was unique. One absolute was dead. Until Einstein (roughly) the universe of Newton was for us the universe. With Einstein it became a universe. The same happened to man. A new "man" was produced, "just as good" and a trifle better, yet contradictory to the old one.[1] Theman became a man, otherwise a conceptual construction, one among the infinity of possible ones.

Granting, for the time being, all that mathematicians say about mathematics (1924), there are two aspects of mathematics which have been neglected.

That which has symbols and propositions is a language. This aspect must be taken into account.[2] Besides, if we free mathematics entirely from theology, mathematics may be viewed as an activity of these bags of protoplasm called "Smith," "Brown," etc. This aspect makes mathematics a form ofbehaviour of man. No psychology of man can ever be valid so long as we disregard entirely this most characteristic behaviour of man. It explains the utter failure of the old mythological psychologies, and the failure of those contemporary students of psychology whose scientific standards and mental age are somewhere B. C.

Lately the natural sciences have firmly established the fact that an organism should be treated "as-a-whole" (Loeb, Ritter, etc.). The theory of relativity has established another fact, that all we know and may know is a "joint phenomenon" of the observer and the observed. Indeed there is no such thing as an "observer," without something to observe, neither such thing as the "observed," without somebody making the observation.

Any inquiry into the affairs of man with any pretense of being scientific (1924),must take into account these two fundamental principles or fail.

Our daily language, and, in most cases, our so-called scientific language together with its logic, originated mostly in a pre-scientific epoch and are largely elementalistic and absolutistic; which must hamper successful reasoning and solutions.

It has been known for some years that we cannot speak sense about man in the old language. Although Wittgenstein has proved this point, he did not show us the way out. The way out is simple. We must form a new vocabulary, which would be in accord with the above-mentioned principles.

Some authors have already used new terms successfully, yet they did not explain the importance of these new terms. For instance the late J. Loeb introduced the term "Tropism" to cover the forced movements of the organism "as-a-whole"; the present writer introduced the term "Time-binding" to cover all the factors "as-a-whole" which made man, a man. We may agree that man differs somehow from animals by the capacity for building this accumulative affair called civilization. In the old way we could argue endlessly about "what made civilization possible." Some say that "thinking" made it, others say that "speech" is responsible (Watson), or writing, etc., etc. As a matter of brute fact, all such statements, takenseparately, are false, because civilization is a joint affair of all of them and an infinity of others, as yet not abstracted.

The new words do perform the task, because they do not split what, for our purpose, should not be separated (Poincaré). This explains why the language of this paper is not our usual one.

The old subject-predicate language and logic veil the inter-relatedness of nature (Whitehead); the new, brings these relations to a sharp focus (Korzybski).

There is a profound difference, indeed, between a man-made green leaf and a non-man-made green leaf. In the first, green color wasadded, it is a "plus" affair, it was "made." In the second, color wasnot added, it is a functional affair, it was not made, it "happened," "became."

Quite obviously, a subject-predicate "plus" language and logic can cover man-made "plus" affairs, but cannot cover functional affairs, "happenings," "becomings"—where, for instance, the natural greenness of the leaf is inherent in the leaf itself, which is not the case with a man-made leaf.

Only a functional logic and language can cover functional natural phenomena (Korzybski). Such logic and language have been built by modern mathematical discoveries (Whitehead, Russell, Keyser, etc.). To treat man at least as fairly as we treat a green leaf, the same methods must be used.

Universal Peace—(be it family, school, industrial, economic, political, scientific, personal, international and what not) depends ultimately on Universal Agreement.

Universal Agreement—is finally based on Rigorous Demonstration. Rigorous Demonstration—absolutely depends on Definitions.

Definitions—are ultimately conditioned by

Correct Symbolism.

Universal Agreement—is finally based on Rigorous Demonstration. Rigorous Demonstration—absolutely depends on Definitions.

Definitions—are ultimately conditioned by

Correct Symbolism.

So, if we want universal agreement, we must start with correct symbolism. Before a theory of correct symbolism may be written down it must already have started with correct symbolism. It must be felt instinctively. A prototype of correct symbolism we may find in mathematics.

A word is a symbol. Before a sign may become a symbol something must exist for this sign to symbolize, else the sign has no meaning; it is not a symbol, not a word, but a noise. For our purpose we may speak, in the rough, of two kinds of existence, namely, the physical existence, somehow connected with persistence, and logical existence. By logical existence we mean in this case a thinkable thought, otherwise free from self-contradiction (Poincaré). A "word" which labels a self-contradictory "idea" is not a word, not a symbol, because it symbolizes nothing; if spoken, it is a noise, or if written, a blot of black on white; it is meaningless, no matter how many thousands of volumes have been written about it.

If we use such noises as significant words, it is a fraud played on the other fellow. Such acts should and will be some day, listed in the criminal codes of civilized countries as among the most harmful crimes against civilization.

With this introduction permanently in mind we may proceed, provided we agree that we will try to talk sense about "man." If this unusual request is granted, our task is not difficult; without it, it is impossible.

Let us imagine a genetic series, father-son-grandson, etc. We start with "Amoeba I" (A1), and end the series with "Albert Einstein" (AE). Somewhere near the end there is an individual, "Adam" (A). All individuals are very "real," and every one of them is different. According to one of the important rules of correct symbolism we label every individual with a different name, so that every individual has one and only one name.

We wish, (it is only our pleasure) to produce two other words "man" and "animal." I said "We wish"; it is so because there is no such thing in the world as "a man" or "an animal." These labels are names for abstractions of high order, for "ideas" and not things. Smith, Brown, Jones, etc., are "realities," objects, but they all are different, and the collective name "man" is given to an idea and not a thing. This point is extremely important, and I would suggest to the reader to be entirely convinced on this point before he proceeds, otherwise he will not be able to follow the rest.

Incidentally we see that the naturalistic, as well as anti-naturalistic creeds are false, because both are based on the false assumption that "a man" or "an animal" is a thing.

If we want to talk sense about the ideas "man" and "animal", wemust have them sharply defined, otherwise confusion must follow. We do not want to produce unnecessary new words; we inquire whether the old terms in which we used to speak about the terms "man" and "animal" will serve our purpose, which is to talk sense. There is one condition, among others, which must be fulfilled, namely the terms must be sharp. We pick any of the old terms, let us say, for instance, the term "thinking."

How do we get this term? We find that we watched the behaviour of Smith, Brown, Jones, etc.; we passed through a mental process of abstraction, generalization, assumption, inference and what not, and in this way we got our term "thinking." We do the same with, let us say, "Fido" (I select Fido because the majority of us know and like dogs). We watch the behaviour of different dogs, Fido I, Fido II, Fido III, etc.; we pass through the same processes of abstraction, etc. and we conclude, "Fido thinks." Obviously the term "thinking" isnot sharp, and because it is not sharp, we must abandon it as useless. We may retain this term for family use, but science is a public activity, and for public use nicknames will not do.

The problem now is such that we want to keep the useful terms "man" and "animal" and we have no terms in which we could talk sense about them. There is only one way out, namely, to produce new terms which will be sharp. As "man" and "animal" are not things but logical entities, the finding of those sharp definitions is a problem of ingenuityonly.

We observe again our genetic series; we note that "man" is an accumulative class of life with a special high rate, in that the son may start where the father ended, and that "animals" are not accumulative, or, if accumulative, they are so with a different and slower rate. With Korzybski we label these two different rates of accumulation "Time-binding" for "man," and "Space-binding" for "animals."

Amoeba I

|

Adam

|

Albert Einstein

|

| I | I | I |

animal

|

man

| |

| Non-accumulative class of life or if accumulative, with a different and slower rate, which we label: "Space-binding" | accumulative class of life, with a rapid rate, which we label: "Time-binding" | |

These differences are sharp.

The foundation for a deductive science of man is thus laid down.

If we inquire into the mechanism of this rapid accumulation (Time-binding, PRt) we should be entitled to expect that we will strike the very core of our problem. This actually happens with most unexpected results.

We must stop here to emphasize, and it cannot be over-emphasized, namely, the power of the method. We cannot talk sense in the old "psychological" terms, therefore we deliberately avoid such terms; we carry on our inquiry in a "queer" engineering way and language, yet the results are deeply psychological. This inquiry unravels to us the deepest secret of man as man, a secret which neither psychology nor philosophy had ever disclosed and capitalized (the last three words representone idea). The explanation is simple: This could not be done before the physico-mathematical revolution of modern science.

THE reader is warned about an extremely important principle entirely disregarded in practice, namely, that what can be shown cannot be said (Wittgenstein). If we show something which we call "a pencil," it is an entirely different affair than when we speak of "a pencil." The content of the first is inexhaustible, the second is a concept, with finite content, fixed by a definition.

The following applies to things, and therefore the actual thing should always be shown.

We take something (anything) let us say a pencil; we show it and ask, "What is this?" This is a process, a chunk of nature, a clog of electricity, a mad dance of electrons; this is something acted upon by everything else, and reacting upon everything else; this is something which is different all the time, something which we can never recognize, because when it is gone, it is gone, etc.

This something which we can never recognize we call an event (Minkowski, Lorentz, Einstein, Whitehead, Planck, Millikan, etc.). The number of characteristics an event has, is infinite.

Yet in this event which we cannot recognize there is something fairly permanent which we can recognize. This we call an object (Whitehead). We label our object with a special symbol which we call a word.

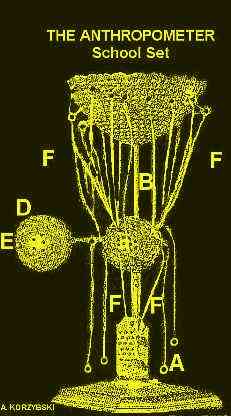

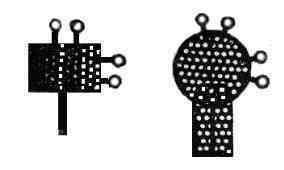

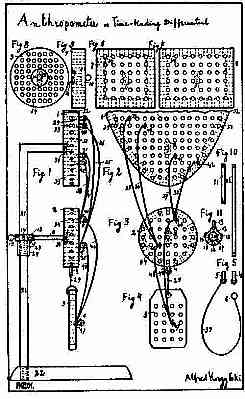

The accompanying picture represents the Anthropometer, a plastic diagram to illustrate what has been said.

C represents the "event"; it is a broken-off paraboloid which indicates extension to infinity, while the holes represent characteristics, infinite in number.

B is the object of finite size with a large, yet finite, number of characteristics.

A is the label—a word. The holes, also, represent characteristics.

What is an object? An object is a first abstraction, a first rough summary, a first integration, etc., of the infinite number of characteristics of the event, into the few characteristics of the object. This process of abstracting is indicated by lines F.

|

We get the meaning of our symbol by defining it, that is by abstracting a second time (F1) from the many characteristics of the object into the still fewer characteristics of the label. The symbol is a second order abstraction. Then follow abstractions of higher orders.

How about Fido? We defined objects in terms of recognition, therefore "who recognizes has objects." It means, by definition, that Fido "has objects." Are his objects the same as ours? Similar, but not the same (D). For instance, we can not recognize our own gloves among a thousand of gloves, but Fido can. Has Fido "symbols"? Yes, he barks at a cat and another Fido "knows" somehow, something. But his symbols are not articulate (E).

We see that Fido's objects (D) are first-order abstractions; what he lacks is the second and higher-order abstractions. It must be remembered that the new language of orders of abstractions has the flexibility and exactness of number series. We could ascribe to Fido many orders of abstractions, but man would have still higher. I take here the simplest case; the other refinements would not alter the method, and this is important.

We see that the difference between "Fido" and "Smith" is in the order of abstractions, and this difference issharp.

Here a crucial question arises. No doubt Fido did the abstracting; does Fido know, and can Fido know that he abstracts? The answer is positive (due to the method): Fido does not know andcannot know

that he abstracts, because it takes science to know that we abstract, and Fido has no science, as a matter of brute fact.

|

This faculty for building higher and higher abstractions is the mechanism of the characteristic rapid accumulation, which makes man a man.

If, for instance, we could see an electron in its flight, the world would be a maze; no law, no order, no intelligence would be possible.

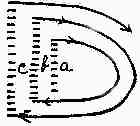

The first nerve, the first dynamic gradient (Professor Child) (a) was not stimulated by all of (b) but only by a small part (c). (a) got the experience of (b) by exploring, summarizing, abstracting the (c's), and so it goes all through life, man included.

Life and "intelligence" and abstracting start together, this being the result of the physico-chemical structure of living organisms. The function builds the organ (Professor Child). The mechanism of the rapid human accumulation is the faculty for higher and higher abstractions, which accelerate its progress at a permanently increasing rate.

Life and "intelligence" and abstracting start together, this being the result of the physico-chemical structure of living organisms. The function builds the organ (Professor Child). The mechanism of the rapid human accumulation is the faculty for higher and higher abstractions, which accelerate its progress at a permanently increasing rate.

The term "abstracting" is used here in the "organism-as-a-whole" way, where "senses" and "mind" are not divided; we know that the old elementalistic methods are not valid.

The complexities of life and of the organism become intelligible in terms of orders of abstractions, and it must be repeated again, that it is immaterial how many orders of abstractions we ascribe to an organism—the method remains the same.

We may illustrate what was said by a simple experimental fact. We all know an electric fan. When the fan is rotating rapidly we do not see the separate blades (a) but we see a disk, a shield (b). "Matter" and "objects" are such shields or disks; in other words a "joint phenomenon" of therotating blades and our abstracting organism. We cannot put our finger through the disk, although itis a fiction, because the rotation of the blades is much more rapid (for one of the reasons) than the velocity of our finger. Similar reasons explain why we cannot put our finger through a table; it takes an X-ray to be able to do so, in some instances.

instances.

instances.

instances.

The Anthropometer shows to the physical eye, that in human economy (A) is not (B) and (B) is not (C) (this must be shown on the Anthropometer); in animal economy (A) is (B) and (B) is (C); in other words, the animal does not discriminate between the three. If man omits to discriminate,he copies the animals in thinking.

This simple fact is the solution of practically all human troubles. The reader should not be misled by the childish simplicity of this all-important issue. As a matter of fact we nearly all, until this day copy Fidos in our thinking, by not being conscious that we abstract. This habit so permeates our old theories and practice, that one has to have the Anthropometer before him for some time to overcome this pernicious habit. Those who copy Fido must be dogmatists, categorists, absolutists, "know-alls"; they must be fanatics, intolerant; when they meet others of their kind, a fight must follow, etc. They do not want to think, they are not interested to investigate, for why should they? They "know it all," they are self-satisfied in their ignorance, they "know" that they "know all," which is all there is to know about it. They will persecute others who think. For them thinking and science are crimes, or, at best, unnecessary waste of time; and, if forced to think, it is a serious pain to them. They take everything for granted, critical thought and the spirit of inquiry is entirely foreign to their makeup.

Man to be a man and think as a man must be a relativist, which is an inevitable consequence of the application of correct symbolism to facts. He knows that he does not know, butmay knowindefinitely more, that his knowledge is only limited by his own ingenuity and nothing else. This feeling liberates his creative faculties, arouses his interest, his energy, builds up his character and puts his strivings on a very high level. His sporting spirit is aroused; he wants to know more; he wants to inquire and think; in fact, with the understanding of the Anthropometer he must think, there is no escape for him, and thinking becomes a pleasure to him as well as a necessity.

This explains, also, the well-known fact that with the Fido-way imposed upon mankind, it was impossible to make a man think. But with the Anthropometer introduced into homes and elementary schools, it is impossible to stop man from thinking.

A man who understands and applies the Anthropometer will never take a word for granted; instead, he will ask indefinitely, "What do you mean?" and this, ultimately, leads to inquiry into facts, correct symbolism, and universal agreement. The important thing is to get the feeling that we abstract, firmly rooted into the minds of the children.

This achieved, the rest follows automatically.

All disputes such as the fight between the vitalists and the mechanists; the modernists and the fundamentalists; naturalists and anti-naturalists; the Newtonians and the relativists, etc., evaporate, since these are mostly due to the objectification of higher abstractions, the Fidoism in our thinking processes.

The elimination of the Fido-ways would affect, in an extremely beneficial manner, our old economic system; it would bring sanity where, at present, there is none.

What is money? Money is a symbol. A symbol for what? For all human Time-binding faculties; animals have it not. No doubt bees producegoods—honey, but these goods of the bees are not wealth until man puts his hands on them. Money is not edible or habitable, it is worthless if the other fellow refuses to take it. The reality behind the symbol is human agreement, or else the value behind the symbol isdoctrinal. Fido does not discriminate between A and B, and B and C (see the Anthropometer). He worships the symbol alone. "In Gold we trust" is his motto, with all its destructive consequences. Man must not forget the reality which is behind the symbol. It is amusing to see how the so-called "practical man" deals, mostly, with fictitious values, for which he is willing to live and die. When he has the upper-hand and ignorantly plays with symbols, disregarding the realities behind the symbols, of course, he drives civilization to disasters. Life is full of them.

We see also the utter folly of anyone making a race to accumulate symbols, worthless in themselves, destroying the mental and moral values which are behind them. For it is useless toown a mentally disorganized world, such "ownership" is a fiction, no matter how stable it may look on paper. Commercialism, as a creed, is such a folly.

Some day even economists, bankers and merchants will understand that such "impractical" works, as the present one, for instance, on the stabilization of doctrinal values, are directly working toward the stabilization of an economic system; which the former, in their ignorance, do their best to keep unscientific and, therefore, unbalanced.

But such thoughts are beyond the Fidos, and the world is drifting rapidly toward further catastrophes.[3]

We may outline a few more, important consequences. The understanding and the training with the Anthropometer would help scientists in all lines of research, for there are no "facts" free from some "doctrine." There are only "facts" with bad logic and facts with good logic. Gross empiricism is a delusion, and he who professes it as a creed is probably more mistaken than the old metaphysicians were.

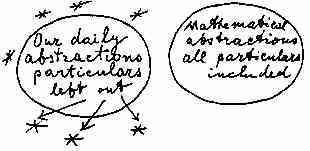

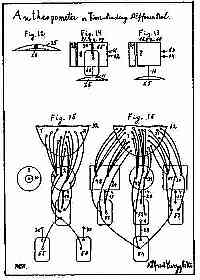

| |

Deduction worksrelatively until we bump our nose on these particulars left out.

|

Deduction worksabsolutely, if correct. We never can bump our nose, because no particular is left out.

|

Mathematical abstractions differ from our daily abstractions by the fact that mathematical abstractions include the particulars, in mathematics we go byremembering (Lambert, Cassirer); the opposite is the case with our daily language, wherein abstractions leave the particulars out. We go by forgetting, until we bump our nose in our deductions on some particular left out.

The majority of our disasters is due to the not knowing or neglecting of this all important issue. The Anthropometer, giving the consciousness that we abstract, brings these issues forcibly home.

We mostly all (mathematicians included) objectify our high abstractions, which is a confusion oforder of abstractions. But mathematics is unique in this respect, that mathematical abstractions have all particulars included, and therefore these objectifications are not dangerous. This explains why mathematicians very seldom show "practicality" in life; they objectify daily abstractions with great assurance in the same way they do with mathematical abstractions, and disastersmustfollow.

The objectification of high abstractions is a terrible danger, because of these particulars left out, but the moment we realize this, we are conscious of it, the danger is over.

If the event has an infinity of characteristics, then, obviously, from an event we can build up an infinity of higher-order abstractions. Because of it the old "negative facts" become a much more fundamental source of knowledge than the old "positive facts" (conventional). Einstein's theory is a brilliant example. When we speak about something, what we actually do, is to exhibit the behaviour of a system of symbols, rather than to say much about this world (Ogden). When the system misbehaves, then we learn something important about this world.

The realization of it, the feeling of it, gives us these wings Couturat was speaking of, and Poincaré was laughing at. It sets man free. The Anthropometer releases man from the old limitations of Fidoism, when shown (not only said. A "knowing class of life" begins with "knowing," therefore, scientific method and science is not a luxury for the privileged few; it is the very thing which differentiates "Smith's" "thinking" from Fido's "thinking." The consciousness of abstracting which is so fundamental for man, is the awareness of a faculty, and inthis special case we can use thisfaculty only when we are aware that we have it.

The Anthropometer shows that the event is an absolute variable, different all the time; the object is arelative variable, different for every observer, the label is a constant, when posited by a definition. It follows that we cannot agree (theoretically) about an object, and cannot disagree on the label.

These undeniable facts lay down the foundation for a positive theory of universal agreement, inherent in the structure of human knowledge. From an event we can abstract an infinite number of abstractions of first and higher orders. Only folly can make us fight for these abstractions, which are only poor selections among the infinity of possible ones. We do not need to doubt human reason, we should distrust our language. There is a world of difference between these two conceptions and attitudes.

The Anthropometer is built upon two fundamental primitive feelings, namely: that we abstract, showing on the Anthropometer "This (A) is not this (B), and this (B) is not this (C)"; while for Fido "This (A) is this (B) and this (B) is this (C)"; all three are one. And that of difference and of countingthe differences (we do not need actually to count them, the feeling is there just the same). Exactness here is not required, although it is always desirable; the feeling that we abstract is all that is needed. This feeling, I repeat again, is the awareness of a circular faculty, and is, therefore, necessary for its exercise.

As a result, universal agreement becomes a possibility. We can give the "scientific temper" to the masses in a very short time. The dreams of Bertrand Russell may become true.

The modern physico-mathematical discoveries become very simple when explained on the Anthropometer. Einstein simply refused to copy Fido, and objectify higher abstractions such as "space" and "time" (Minkowski) and "matter" (Whitehead).

III

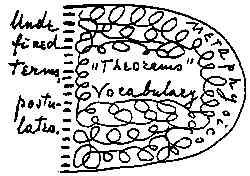

AS SHOWN before, the meaning of a label must be given by a definition. This fact gives us the means to investigate the structure of all human knowledge.

Whenever and wherever we start, we must start with a set of words which are undefined, because we have, by assumption, no more words to define them. This means that human knowledge, at every stage, presupposes knowledge of these few undefined words. This is called, in logical terms, the circularity of human knowledge.

We have never before faced this issue candidly, and it has ever been responsible, as it is today, for most of all intellectual gloom and skepticism. This inherent structure of human knowledge was called the "weak spot" of knowledge, which, of course, it is not.

It cannot be theoretically denied that human knowledge is a faculty such that the son can start where the father ended; therefore it always should start from the latter-end (1924) and not from the beginning. This fact, as yet entirely ignored theoretically, shows that the naturalistic philosophies should be reversed as to logic and order when they tackle the problem of man.

The gross empiricists, overwhelmed with horror against the old metaphysics, went to the other extreme, into a mythology equally false to facts.

When we inquire indefinitely, "What do you mean?" accidentally we spoil every nice "talky-talk"; but we also come to a set of undefined terms, which are postulates. All the rest of our vocabularies (not names for things) are theorems, logical necessities of the starting set of terms strictly interwoven with the metaphysics of the maker of the vocabulary. It may be mentioned that a babe, before he begins to understand anything and to revise his feelings about the world around himself, has alreadyhis metaphysics aggravated by the metaphysics of his parents, teachers, etc., away back to our savage ancestors. Of course, these metaphysics are false to facts, but just the same it is first as to order.

We see that all human knowledge is geometrical in structure (I might say mathematical, but for serious reasons, I prefer to say geometrical). Somewhere at the border line there is the metaphysics. The system is strictly interdependent and bound up by "Logical Destiny," to use this beautiful expression of Professor Keyser.

The expression "circularity of human knowledge," was used here in its logical sense, which is misleading if taken literally. We muststart somewhere, somehow, anywhere, anyhow, with a set of undefined terms, then go ahead, come back, revise our base (a) for (b), go ahead again, revise our base (b) for (c), go ahead again, and so on endlessly. Human knowledge is inexhaustible. No set is undefined absolutely, but only relatively so.

In practice, things are much more complicated because we seldom, if ever, have one vocabulary. But we must untangle first the simplest theoretical issue. The vocabularies (silent postulates) imply the theorems, the theorems imply the postulates. He who accepts uncritically the vocabulary made by X, accepts unwillingly and unbeknowingly X's metaphysics. This fact is of very great importance. If we accept the vocabulary made by X and the metaphysics made by Y, we are lost in inconsistency, the world is an ugly mess, unknown and unknowable. This mess, which is nearly always followed up by rampant pessimism, is the necessary consequence of the misunderstanding of what is here explained. With understanding, our troubles vanish, the world remains unknown (because the Fidos have so long persecuted science) but it becomes knowable.

In practice, things are much more complicated because we seldom, if ever, have one vocabulary. But we must untangle first the simplest theoretical issue. The vocabularies (silent postulates) imply the theorems, the theorems imply the postulates. He who accepts uncritically the vocabulary made by X, accepts unwillingly and unbeknowingly X's metaphysics. This fact is of very great importance. If we accept the vocabulary made by X and the metaphysics made by Y, we are lost in inconsistency, the world is an ugly mess, unknown and unknowable. This mess, which is nearly always followed up by rampant pessimism, is the necessary consequence of the misunderstanding of what is here explained. With understanding, our troubles vanish, the world remains unknown (because the Fidos have so long persecuted science) but it becomes knowable.

With all of this permanently in mind, it is easy to understand anybody else, just as a mathematician when he hears a theorem, he knows usually from which geometry it is taken.

If we do not understand the above, we are slaves; if we know it, we are free, because we can select our master (Keyser, Poincaré).

The geometrical structure of human knowledge shows that man is extremely logical, if we grant him his conscious and unconscious premises (language). Whoever has any doubts about all of the mentioned issues should visit an asylum, where he would see the working of this general theory in its nakedness. In daily life and in semi-insane cases the issues are veiled by customs, habits, overlapping vocabularies, and other doctrinal complications. It is known that "insane" people are extremely logical. In many instances "insanity" is cured by making the unconscious premises conscious. Psychiatry, as yet, has no preventive methods. The Anthropometer is such a preventive educational method against many cases of insanity and different unbalanced states, due to inherited or inhibited false doctrines. A man full of false doctrines cannot be a perfectly normal, healthy and useful man; neither can he copy Fido in his thinking processes without somehow registering it to the detriment of society and himself.

When someone claims to be a "Napoleon" we lock him up. How about the majority of us? Do we not fancy that we are what we are not? That is rather a serious question.

The psychiatrists have all the time to fight "absolutism" and "dogmatism," which in many instances are responsible for different forms of insanity. They do so without the full understanding of the mechanism of it.

The whole advancement of science and civilization shows that this theory is true, but as we did not know explicitly the structure of human knowledge, every revision from (a) to (b) and from (b) to (c) (see page 21) etc., was always painful and slow. We see that, as the structure of the atom is reflected in a grandiose manner in the structure of the universe, so is the structure of the knowledge of the individual man reflected in the collective knowledge of mankind called science, and vice versa.

IV. Consequences and Applications

AT THE present stage of our inquiry it is impossible to foresee all the consequences and applications of this general theory by means of the Anthropometer, but some of them are manifest from the beginning, and are manifold and weighty. I will summarize them, roughly only, as material for thought and further analysis.

It must be emphasized again that merely talking about the Anthropometer will not help much. This prototype of the event and the object and the label must be shown. The moment we point our finger at them and say "this," it cannot be covered by words, and it economizes thousands of words at once. Whoever disregards this positive condition and misses the benefit of it, should not blame the theory and the Anthropometer, but his disregard of a vital condition and issue. The old Fido-way is so deeply rooted in our theories, practice, habits, systems, etc., that although I have had it on my desk for more than a year, my own Fidoism shocks me far too often. In a century or so, of course, we shall not need it, but such is not the case at present.

Some of the consequences are educational and scientific, some are suggestions for activities. We will start with the educational and scientific ones.

The inherent circularity and geometrical structure of human knowledge proves the interconnection of our vocabularies with our metaphysics. We see, that if we want humans to be humans and think as humans, we must start our education from the latter-end (1924) by beginning with modern "metaphysics" of Planck, Einstein, Whitehead, Russell, Keyser, etc., made possible by the understanding of the Anthropometer and the structure of human knowledge.

We would then find, at once, the interest of the masses aroused, and thinking would start on an unprecedented scale, with all its beneficial results. The "scientific temper" would overrun mankind in a few years, facts and correct symbolism would count, and the exponential law PRt would begin to work properly.

Man is ultimately a doctrinal being. Even our language has its silent doctrines, and no activity of man is free from some doctrines, so that the kind of metaphysics a man has, is not of indifference to his world outlook and his behaviour.

We cannot expect when we force a dynamic being into the patterns of Fido static doctrines, that we will get anything else but an unbalanced being in an unbalanced civilization.

The Anthropometer should be introduced into elementary schools and we should start our education with it, everywhere. We must teach a small modern scientific vocabulary and train our children to think habitually in these new terms; which automatically carry with them a new non-absolutistic world conception. Such simple and mechanical means (they must be mechanical and simple if we hope to give them to the masses) would impart to all mankind, not the knowledge, but thecultural results of university training. Such methods, the complete reversal of the old, would stop Fido-ways in theory and practice.

The language of "concepts" is very difficult because that is an elementalistic, absolutistic term (as auxiliary it may be useful) and will not do as our fundamental term. This doctrine is very difficult to teach even to university students, to say nothing of the masses. The language of "abstractions of different orders" is not an elementalistic term; it is a "joint-phenomenon," "organism-as-a-whole" modern new term; it is natural to man, it can be shown to him, and is easily grasped by children and people of very low mentality when shown on the Anthropometer.

We see that modern philosophers have heavy duties and responsibilities toward mankind; heavier, perhaps, and more important than the duties and responsibilities of engineers and doctors. With the modern physico-mathematical discoveries and mathematical discoveries, as those of Whitehead, Russell, the "doctrinal function" of Keyser, etc., "philosophy" has ceased to be a divertisement of the few, it has become as vital an inherent factor in all human life, as air, water, and sunshine. There are communities who have very little to do with engineers or doctors, but no community in the world is free from some kind of "philosophy." Among savage tribes we see how doctrines have prevented entirely any progress at all. The more civilized races have advanced simply because they were more rebellious, and never could stick to an unrevised doctrine for too long.

This is why we have had this semblance of civilization at all! It is not enough to discard philosophy entirely, on the ground that most of it is foolish. Granted our old philosophies were foolish enough, whoever thinks he can discard them entirely without supplanting them by others, sometimes equally foolish, deludes himself. The problems at hand require philosophy, and ignorant vagaries will not do. It is about time that mankind should hold the philosophers responsible. Ignorance is not an excuse.

It may as well be admitted that our old educational methods would have to be reversed. Babies should start their education playing more with microscopes than toys. Before they learn to spell they should firmly feel, at least, the structure of "matter," the structure of human knowledge, and the mechanism of human symbolism. Then they would be equipped to be humans.

Science is not a luxury for the few, but as it leads to the consciousness that we abstract, science and scientific method is precisely that, which makes man think and behave as man.

Non-scientific, half-education (in the sense of 1924, which we could, maybe, consider "scientific education" in the sense of 300 B.C.) is not a boon to mankind in 1924, far from it. That is very natural in the meantime. The conditions, environment, social inheritance, racial experience, other complications, with all accompanying andnovel nervous and mental pressure upon man in 1924, are entirely different from these in 300 B. C. Is his mental, nervous resistance and health properly taken care of? Are our educators and doctors themselves modern men? Sad to say the answer is NO. We still educate man, drug him with doctrines thousands of years old, doctrines which are inconsistent and false to facts. We still keep him in a savage-made universe. This deep discrepancymust unbalance him, and periodically unbalance his institutions. The sooner we understand this and modernize the antiquated branches of knowledge, the better for all of us. There is hope for us, if we stop folly. Our old doctrines do not work even with savage tribes, as practice shows. From the modern point of view the savage tribes do not gain anything by passing from one kind of savage-made doctrines to another set of savage-made doctrines. Experiments should be made, by taking some newly-born from different savage tribes, placing such children in highly cultured scientific families and give them full scientific education, and see what would happen. The new doctrines would work maybe, where the old failed.

The Anthropometer presents a synthesis of modern scientific strivings in a form ready for application.

In the old way we delude ourselves talking about the "education of the masses," and in the old way it is hopeless. What we need most at present and what could be accomplished very quickly is the re-education of the educated. A proper insistence by the scientists, and a few books for this purpose would perform the task. The understanding of the Anthropometer shifts the center of gravity from something which is impossible to something which is possible.

With a re-educated educated class the world would soon become a different place to live in.

The benefits of new terms are that occasionally they throw a new light on old problems, or quite often they help in settling, in a positive way, old controversies. When some controversial questions are settled the world accepts them quickly. What was roughly known but ignored, because veiled by the old language is brought by the new language to a sharp focus. After the results are obtained, they may be explained in any language, but the results, in most cases, could not be gotten in another way.

As a matter of fact, civilization has advanced in the shape of the diagram given on page 21, but as we did not know that this was the inherent structure of human knowledge, every revision of our assumptions was slow and accomplished with great suffering and bewilderment. The creative scientists and teachers were persecuted and hampered, mankind has paid a hideous price. The new understanding will stop persecution and propaganda of any kind.

The popular introduction of the Anthropometer would also prevent the publication of nine-tenths of books and the delivery of the majority of speeches, inasmuch as most of them are based on Fido-ways. Such elimination would relieve us of a great amount of useless ballast.

We must repeat here that the theories of relativity have a still more general underlying theory, namely, the general theory of time-binding. As this theory is so general it is therefore easy to grasp and teach, even to children. It explains the refusal to accept high-order abstractions, such as "matter," "space," and "time," for first order abstractions, which they are not. This is the minimum of science (1924) with which each babe should start its education.

There are a few interesting points about "matter," "space" and "time." Taken separately they are abstractions of high order and not objects, or abstractions of first order. If we objectify the high abstraction, we get a fanciful universe, self-contradictory, a nature which is against human nature. Being logical, we invent something supernatural to account for a nature against human nature. If "time" is an object, if it has objective existence, then, obviously, it must have, as all objects have, a beginning and an end; then the universe was made, it must have a "beginning of the beginning" (old "essences"), etc., etc., and the whole old anthropomorphic mythology follows, by a purely logical process.

But if "time" is an abstraction of high order and not an object (first order abstraction), otherwise, if it does not exist as an object, then, obviously, something which does not exist cannot have a "beginning," or a "beginning of the beginning," the universe was not "made," etc. It just was, is, and will be. Obviously the "primal substance" may quite happily be a myth in such a universe of transformation; we cannot exhaust it in either direction.

Our universe is timeless. In another language, it is eternity in time, or, still in another language, infinity of times (this is a generalization of experimental time). When times are very rapid we nervously summarize times, and feel "time," a "duration." The "infinity of times" is nothing else, when translated in still another language, than the law of conservation of energy. Incidentally it proves the existence of actual infinity.

The above explanations were given because the old Fido-ways are omnipresent. In a way they permeate all mankind, and they must lead us to most acute mental disorders, reflected in behaviour. I do not know any other phase of science in the whole history of civilization which would have a more profound and beneficial influence upon the daily life of the man on the street, than the modern advancement of mathematical and physico-mathematical sciences, when given to the masses and applied in education.

This understanding clears up another old fallacy. We are accustomed to hear that the old mythologies are somehow "primary" with man. We see clearly that it is not true. Those mythologies are "secondary" with man. What was primary is the objectification of high abstractions, the Fido-ways in our thinking processes. Once this is eliminated by the Anthropometer, all the old vicious fictions automatically vanish.

If we confuse the orders of abstractions; if we fancy that the high abstractions are first-order abstractions, which they are not, then we get "absolute matter," "absolute space," and "absolute time." If the world is made up of "absolute matter," "absolute space," "absolute time" then of course such a structure cannot account for "mind" and what not. The number of possibilities in such a universe are too limited, etc., etc., and all the rest follows. But if the world is made up of "quanta," "fields," etc., then all we see, we feel, we know and can know are averages, summaries, abstractions of different orders, etc., etc. Only a language of processes, transformations, variables, functions, integration, abstractions of different orders, probabilities, etc., etc., can account for such a universe. Mathematics considered as an activity of the human organism, reflects in its structure and form the structure and form of the universe. Being a language, it is the universal tongue.

In such a universe all we deal with are combinations of high orders ("Matter" made up of molecules, molecules of atoms, atoms of electrons, and so on, probably).

How the combinations of high order grow, as to numbers of possibilities, an instance taken from the Principles of Science by Jevons will show. This simplest possible case which is far, far away from any "simplicity" in nature, will show.

"The successive orders of the powers of two have, then, the following values, so far as we can succeed in describing them:

First order ......................................................... 2

Second order ..................................................... 4

Third order ........................................................ 16

Fourth order ................................................ 65,536

Fifth order number expressed by 19,729 figures.

Sixth order number expressed by figures, to express the number of which figures would require about 19,729 figures."

Second order ..................................................... 4

Third order ........................................................ 16

Fourth order ................................................ 65,536

Fifth order number expressed by 19,729 figures.

Sixth order number expressed by figures, to express the number of which figures would require about 19,729 figures."

By way of contrast Jevons gives us "that the almost inconceivably vast sphere of our stellar system if entirely filled with solid matter, would contain more than about 68•1090 atoms, that is to say, a number requiring for its expression 92 places of figures. Now, this number would be immensely less than the fifth order of the powers of two."

Due to the modern knowledge of the structure of the world we see that practically everything becomes possible, and may be understood, no matter when. The feeling of these issues, with the lack of understanding of the simple law of growth of the higher order combinations, gives, I think, the base for mystical feelings, which vanish as such, once these issues are understood. We can know, never mind when; all the rest is a matter of method and science. In this way the unknowable becomes knowable. Correct symbolism covers all these facts, also, and leads to the same conclusions.

The concept of order is fundamental, not only because it underlies all mathematics but, also, because it is easily and obviously translated in terms of senses. This gives a base for a scientific vocabulary.

The savage-made language of "cause" and "effect" has also order in it, only it is a very short series—it is a two-term relation. Yet, in the world around us, there is no such thing in existence as a two-term relation, and therefore when we use a two-term relation, cause-effect, these two terms are overloaded with non-crystallized "thought" (emotion), hence metaphysics of the wildest kind. Science expands the series into an indefinite number of members. Old ignorance and metaphysics go.

The expansion of this series is the coefficient of our knowledge.

The theory, as expounded in this paper, seems to suggest directions in which some activities could be started.

There seems to be no doubt that the recent physico-mathematical and logic-mathematical advancement of science is affecting all branches of human knowledge in many unexpected directions. It seems without question, that the scientists could not deal with these problems without the help of professional mathematicians. If the mathematicians refuse to cooperate with other branches of science, Human Engineering included, it will probably take one or more generations before the whole beneficial effect of modern discoveries would be felt in education and life.

The situation today is such that, in many serious instances, naturalists who know "facts" speak nonsense quite happily, about them. The mathematicians who alone speak sense, know very little or nothing about facts. The results are: slow advance, groping in the dark, thousands of false doctrines, and endless arguments in vacuo. Science is a joint phenomenon of logic and "facts"; as there are no "facts" free from some doctrine, therefore science should be carried on as a joint phenomenon. Experimentalists, for example, should have very able and creative mathematicians who would work at logic and language, and they should work together, jointly. Life is too short for one to be a specialist in several lines at once; science has outgrown the individualistic epoch, it must become a group activity.

The situation today is such that, in many serious instances, naturalists who know "facts" speak nonsense quite happily, about them. The mathematicians who alone speak sense, know very little or nothing about facts. The results are: slow advance, groping in the dark, thousands of false doctrines, and endless arguments in vacuo. Science is a joint phenomenon of logic and "facts"; as there are no "facts" free from some doctrine, therefore science should be carried on as a joint phenomenon. Experimentalists, for example, should have very able and creative mathematicians who would work at logic and language, and they should work together, jointly. Life is too short for one to be a specialist in several lines at once; science has outgrown the individualistic epoch, it must become a group activity.

All our doctrines should be revised and correct symbolism should be applied to facts. The old philosophy is dead in disgrace, the world is without co-ordinating guidance. To be fair to philosophers, no single person nowadays could perform this co-ordinating work alone. It again must become a group activity.

If we want to avoid complete mental anarchy, which must be followed up some day by grave disturbances in our behaviour, this problem of revision and co-ordination must be our urgent and immediate task. The people of the world have lost the old faiths in their theories, their leaders, and themselves; this state, again is another phase of other creeds as yet not crystallized. Only heroic measures can save us from still worse turmoils.

When, for instance, biologists make statements about mathematics, or mathematicians make statements about biology, such statements are always short somewhere on knowledge, they never are competent. Statements should be made by biologists on biology, but with the full understanding of other branches of knowledge; by mathematicians on mathematics, but also withfull understanding of other achievements.

Such work could be done only and exclusively by a permanent body of the world's best scientists being relieved from all other duties who, after getting acquainted with each other's specialities, would work together on the revision of language and doctrines, and would prepare this co-ordination of knowledge. Such a permanent body could issue a yearly or quarterly journal which would give to mankind the revised and co-ordinated doctrines of each "present" day.

Such a method would allow mankind to start every generation where the last one left off, and the progress of civilization would follow the exponential law PRt. A copy of this general doctrinal summary should be placed in the hands of every teacher throughout the world, by legislation if need be. There is no doubt that if scientists themselves insist upon some such plan, mankind would accept it. After all, a united opinion of those who, in the major part, are the driving force of civilization, is irresistible. Scientists would start with such an institution a new period of human history which would be called the "scientific era." This body might be called the "Senate of Humanity" (this name was suggested to me by Professor A. Vasiliev, and I gratefully acknowledge it).

If the peoples of the world were told that the best scientists of the world are working on their problems they would settle down and wait, some hope would be restored, otherwise they will not wait. The publications of the "Senate of Humanity" would be stripped of technicalities so that the general public would understand them. They would save an enormous amount of work to scientists and laymen by giving short, yet reliable, informations in an already co-ordinated andrevised form. With these budgets of knowledge, not of paradoxes, mankind would come gradually out of the Fido era, into the scientific era.

We need not delude ourselves. The most important hindrances, in the old ways, are found in language and the logics; these problems would remain the most important for a long time to come, and the mathematicians would have to play nolens volens, a most conspicuous rôle, a rôle worthy of their science.

It follows from the geometrical structure of human knowledge, that the solution of all human problems lies in frankly putting all branches of human endeavor upon a postulational base. Postulational treatment gives us unique benefits, among others, it facilitates inspection, gives clarified systems of doctrines, and unifies all other methods. Our debates would become limited to experimental testing of our sets of postulates.

It may be mentioned that such a library is being established in New York City under the name of "International Library of Human Engineering" (Principia Scientiæ Hominis), which will originate a deductive science of man, and deductive natural and other sciences.

This library will be at present under the editorship of one mathematician and one engineer, with an advisory board of scientists from all countries in all branches of science. For geographical and linguistic reasons, local national boards of co-editors will also be formed.

Until the Senate of Humanity is organized, this library with its international scientific boards, will be the research and organizing center for the future permanent international body of scientists. Its publications would be the handbooks for the future chairs of Human Engineering which sooner or later must be established in all important universities of the world. Human Engineering, as every other branch of engineering, would be based on mathematical methods.

Such is the outline of immediate constructive steps which could be taken. The problems at hand are manifold, weighty, and difficult, beyond the power of any single man to deal with. A great deal of responsible preparatory work must also be accomplished. Such work of course must be a group activity, and it is hoped that the international advisory boards of the library will be able to accomplish a good deal of this preparatory work.

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY

SCIENCE, METHOD

BROAD, C. D. Scientific Thought. London & N. Y.

CASSIRER, E. Substance and Function and Einstein's Theory of Relativity. Chicago.

CAMPBELL, N. R. Physics, The Elements. Cambridge.

ENRIQUES, FEDERICO. Problems of Science. Chicago.

JEVONS, W. S. The Principles of Science. London.

MACH, E. Science of Mechanics. Chicago. Conservation of Energy. Chicago. Scientific Lectures.Chicago. Space and Geometry. Chicago. The Analysis of Sensations. Chicago.

OGDEN, C. K. The Meaning of Meaning. London & N. Y.

POINCARE, H. The Foundations of Science. New York.

CASSIRER, E. Substance and Function and Einstein's Theory of Relativity. Chicago.

CAMPBELL, N. R. Physics, The Elements. Cambridge.

ENRIQUES, FEDERICO. Problems of Science. Chicago.

JEVONS, W. S. The Principles of Science. London.

MACH, E. Science of Mechanics. Chicago. Conservation of Energy. Chicago. Scientific Lectures.Chicago. Space and Geometry. Chicago. The Analysis of Sensations. Chicago.

OGDEN, C. K. The Meaning of Meaning. London & N. Y.

POINCARE, H. The Foundations of Science. New York.

MATHEMATICS, MATHEMATICAL PHILOSOPHY, LOGIC

BALDWIN, J. M. Thought and Things, 3 Vols. London, New York.

BONOLA, R. Non-Euclidian Geometry. Chicago.

BOOLE, GEORGE. Laws of Thought. Chicago.

BRUNSCHVIC. Les Etapes de la Philosophie Mathématique.

CAJORI, F. A History of Mathematics. London, New York.

CANTOR, G. Contribution to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers. Chicago.

COUTURAT, L. The Algebra of Logic. Chicago.

DEDEKIND, R. Essay on Number. Chicago.

HUNTINGTON, E. V. The Continuum. Harvard Press.

KEYNES, J. M. .A Treatise on Probability. London, New York.

KEYSER, C. J. The Human Worth of Rigorous Thinking. Columbia Univ. Press.

KEYSER, C. J. Mathematical Philosophy. E. P. Dutton, N. Y.

LEIBNIZ. The Early Mathematical Manuscripts of Leibniz.Chicago.

LEIBNIZ. New Essays Concerning Human Understanding.Chicago.

LEWIS, C. I. .A Survey of Symbolic Logic. Univ. of California Press.

LOBACHEVSKI, N. The Theory of Parallels. Chicago.

MANNING, H. P. Geometry of Four Dimensions. New York.

RUSSELL, B. The Principles of Mathematics. Cambridge. Scientific Method in Philosophy. Chicago.The Problems of Philosophy. New York. Mysticism and Logic. New York. Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy.London, New York.

SHAW, J. B. Lectures on the Philosophy of Mathematics.Chicago.

SOMMERVILLE, D. M. Y. Non-Euclidian Geometry. London, Chicago.

WEATHERBURN, C. E. Elementary Vector Analysis. London, Chicago. Advanced Vector Analysis.London, Chicago.

BONOLA, R. Non-Euclidian Geometry. Chicago.

BOOLE, GEORGE. Laws of Thought. Chicago.

BRUNSCHVIC. Les Etapes de la Philosophie Mathématique.

CAJORI, F. A History of Mathematics. London, New York.

CANTOR, G. Contribution to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers. Chicago.

COUTURAT, L. The Algebra of Logic. Chicago.

DEDEKIND, R. Essay on Number. Chicago.

HUNTINGTON, E. V. The Continuum. Harvard Press.

KEYNES, J. M. .A Treatise on Probability. London, New York.

KEYSER, C. J. The Human Worth of Rigorous Thinking. Columbia Univ. Press.

KEYSER, C. J. Mathematical Philosophy. E. P. Dutton, N. Y.

LEIBNIZ. The Early Mathematical Manuscripts of Leibniz.Chicago.

LEIBNIZ. New Essays Concerning Human Understanding.Chicago.

LEWIS, C. I. .A Survey of Symbolic Logic. Univ. of California Press.

LOBACHEVSKI, N. The Theory of Parallels. Chicago.

MANNING, H. P. Geometry of Four Dimensions. New York.

RUSSELL, B. The Principles of Mathematics. Cambridge. Scientific Method in Philosophy. Chicago.The Problems of Philosophy. New York. Mysticism and Logic. New York. Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy.London, New York.

SHAW, J. B. Lectures on the Philosophy of Mathematics.Chicago.

SOMMERVILLE, D. M. Y. Non-Euclidian Geometry. London, Chicago.

WEATHERBURN, C. E. Elementary Vector Analysis. London, Chicago. Advanced Vector Analysis.London, Chicago.

(35)

WHITEHEAD, A. N. and B. RUSSELL. Principia Mathematica. Vol. 1. Cambridge.

WHITEHEAD, A. N. An Introduction to Mathematics. New York. The Organization of Thought Educational and Scientific. London. An Inquiry Concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge.Cambridge. The Concept of Nature. Cambridge. The Principle of Relativity. Cambridge.

WINDELBAND, W. (Editor). Logic. London, New York.

WITTGENSTEIN, L. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London, New York.

YOUNG, J. W. A. (Editor). Monographs on Topics of Modern Mathematics.London and New York.

YOUNG, J. W. Lectures on Fundamental Concepts of Algebra and Geometry. New York.

WHITEHEAD, A. N. An Introduction to Mathematics. New York. The Organization of Thought Educational and Scientific. London. An Inquiry Concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge.Cambridge. The Concept of Nature. Cambridge. The Principle of Relativity. Cambridge.

WINDELBAND, W. (Editor). Logic. London, New York.

WITTGENSTEIN, L. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London, New York.

YOUNG, J. W. A. (Editor). Monographs on Topics of Modern Mathematics.London and New York.

YOUNG, J. W. Lectures on Fundamental Concepts of Algebra and Geometry. New York.

THE THEORIES OF RELATIVITY.

BIRD, J. M. Einstein's Theories of Relativity and Gravitation.New York.

BIRKHOFF, G. D. Relativity and Modern Physics. Harvard University Press.

BOLTON, L. An Introduction to the Theory of Relativity.New York.

CARMICHAEL, R. D. The Theory of Relativity (postulational) 2nd Edition. London, New York.

CARR, H. W. The General Principle of Relativity (Philosophical). London, New York.

CUNNINGHAM, E. Relativity, The Electron Theory and Gravitation.London, New York.

EDDINGTON, A. S. Space, Time and Gravitation. Cambridge. The Mathematical Theory of Relativity.Cambridge.

EINSTEIN, A. Relativity. N. Y. The Meaning of Relativity. Princeton Univ. Press. Sidelights on Relativity. N. Y.

FREUNDLICH, E. The Foundation of Einstein's Theory of Gravitation.N. Y. The Theory of Relativity.N. Y.

KOPFF, A. The Mathematical Theory of Relativity. N. Y.

MOSZKOWSKI, A. Einstein, the Searcher. N. Y.

NORDMANN, C. Einstein and the Universe. N. Y.

NUNN, T. P. Relativity and Gravitation. London and N. Y.

SCHLICK, M. Space and Time. Oxford Univ. Press.

WEYL, H. Space-Time-Matter. N. Y.

WHITEHEAD, A. N. The Principle of Relativity. Cambridge.

WILSON, E. B. The Space-Time Manifold of Relativity. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Science.

VASILIEV, A. V. Space, Time, Motion. (Historical). N. Y.

BIRKHOFF, G. D. Relativity and Modern Physics. Harvard University Press.

BOLTON, L. An Introduction to the Theory of Relativity.New York.

CARMICHAEL, R. D. The Theory of Relativity (postulational) 2nd Edition. London, New York.

CARR, H. W. The General Principle of Relativity (Philosophical). London, New York.

CUNNINGHAM, E. Relativity, The Electron Theory and Gravitation.London, New York.

EDDINGTON, A. S. Space, Time and Gravitation. Cambridge. The Mathematical Theory of Relativity.Cambridge.

EINSTEIN, A. Relativity. N. Y. The Meaning of Relativity. Princeton Univ. Press. Sidelights on Relativity. N. Y.

FREUNDLICH, E. The Foundation of Einstein's Theory of Gravitation.N. Y. The Theory of Relativity.N. Y.

KOPFF, A. The Mathematical Theory of Relativity. N. Y.

MOSZKOWSKI, A. Einstein, the Searcher. N. Y.

NORDMANN, C. Einstein and the Universe. N. Y.

NUNN, T. P. Relativity and Gravitation. London and N. Y.

SCHLICK, M. Space and Time. Oxford Univ. Press.

WEYL, H. Space-Time-Matter. N. Y.

WHITEHEAD, A. N. The Principle of Relativity. Cambridge.

WILSON, E. B. The Space-Time Manifold of Relativity. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Science.

VASILIEV, A. V. Space, Time, Motion. (Historical). N. Y.

THE NEWER PHYSICS.

BORN, M. The Constitution of Matter. London. New York.

COMSTOCK, D. E. and L. T. TROLAND. The Nature of Matter and Electricity. New York.

GRAETZ, L. Recent Developments in Atomic Theory. New York.

HAAS, A. The New Physics. New York.

KAY, G. W. C. The Practical Application of X-Rays. New York.

LORING, F. H. Atomic Theories. New York.

COMSTOCK, D. E. and L. T. TROLAND. The Nature of Matter and Electricity. New York.

GRAETZ, L. Recent Developments in Atomic Theory. New York.

HAAS, A. The New Physics. New York.

KAY, G. W. C. The Practical Application of X-Rays. New York.

LORING, F. H. Atomic Theories. New York.

(36)

PLANCK, M. The Origin and Development of the Quantum Theory. Oxford.

REICHE, F. The Quantum Theory. New York.

RUSSELL, B. The A B C of Atoms. London. New York.

SOMMERFELD, A. Atomic Structure and Spectral Lines. New York.

STOCK, A. The Structure of Atoms. New York.

REICHE, F. The Quantum Theory. New York.

RUSSELL, B. The A B C of Atoms. London. New York.

SOMMERFELD, A. Atomic Structure and Spectral Lines. New York.

STOCK, A. The Structure of Atoms. New York.

PSYCHIATRY

ADLER, A. Organ Inferiority and its Psychical Compensation.Washington.

The Neurotic Constitution.

DANA, C. L. Psychiatry in its Relation to Other Sciences.N. Y.

FREUD, S. Totem and Taboo. New York. General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. New York.

FOREL, A. Ants and some other Insects. Chicago.

GRASSET, J. The Semi Insane and the Semi Responsible.New York.

VON HUG HELLMUTH, H. A Study of the Mental Life of the Child. Washington.

JELLIFFE, S. E. Diseases of the Nervous System (with Dr. Wm. A. White). Technique of Psychoanalysis. Washington. The Symbol as an Energy Container, J. of N. and M. D. Vol. 50, No. 6.Emotional and Psychological Factors in Multiple Sclerosis. Ass. for Research in Nerv. and Ment. Dis. 1921. The Parathyroid and Convulsive States. N. Y. Med. J., Dec. 4, 1920. Multiple Sclerosis and Psychoanalysis. A. J. Med. Sc. May, 1921. Paleopsychology. Psychoanalytical Review. Vol. X, No. 2.

MEYER, A. Objective Psychology or Psychobiology. J. A. Med. Ass. Sept. 4, 1925. The Contribution of Psychiatry to the Understanding of Life Problems. Address. What do Histories of Cases of Insanity Teach Us Concerning Preventive Mental Hygiene During the Years of School Life. The Psychological Clinic Press. Philadelphia.Inter-Relations of the Domain of Neuropsychiatry.Archives Neur. and Psychiatry. Aug. 1922.The Philosophy of Occupation Therapy. Arch. of Occup. Therapy, Vol. 1, No. 1.

KEMPF, E. The Autonomic Functions and the Personality.Washington.

WHITE, Wm. A. Outlines of Psychiatry. Washington. Foundations of Psychiatry. Washington.Mechanism of Character Formation. New York. Principles of Mental Hygiene. New York. Insanity and the Criminal Law, New York. The Mental Hygiene of Childhood. Boston. Thoughts of a Psychiatrist on the War and After. New York. The Modern Treatment of Nervous and Mental Diseases (2 Vols.). (With Dr. Jelliffe.) Text-book of Diseases of the Nervous System.(With Dr. Jelliffe.) An Introduction to the Study of the Mind.Washington. Contribution of Modern Psychiatry to General Medicine. Mental Mechanism. Washington. The Behavioristic Attitude. Reprint 101. Nat. Comm. For Mental Hygiene. New York. The New Functional Psychiatry. Archives of Diagnosis, Oct., 1910. Principles Underlying The Classification of Diseases of the Nervous System. J. A. Med. Ass., March 11, 1916.Psychoanalysis and the Practice of Medicine.J. A. Med. Ass. June 2, 1917. Underlying Concepts in Mental Hygiene. Reprint 4 Nat. Comm. for Mental Hygiene. New York. The Meaning of the Mental Hygiene Movement. Publ. No. 17. Massachusetts Soc. for Mental Hygiene. Existing

The Neurotic Constitution.

DANA, C. L. Psychiatry in its Relation to Other Sciences.N. Y.

FREUD, S. Totem and Taboo. New York. General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. New York.

FOREL, A. Ants and some other Insects. Chicago.

GRASSET, J. The Semi Insane and the Semi Responsible.New York.

VON HUG HELLMUTH, H. A Study of the Mental Life of the Child. Washington.

JELLIFFE, S. E. Diseases of the Nervous System (with Dr. Wm. A. White). Technique of Psychoanalysis. Washington. The Symbol as an Energy Container, J. of N. and M. D. Vol. 50, No. 6.Emotional and Psychological Factors in Multiple Sclerosis. Ass. for Research in Nerv. and Ment. Dis. 1921. The Parathyroid and Convulsive States. N. Y. Med. J., Dec. 4, 1920. Multiple Sclerosis and Psychoanalysis. A. J. Med. Sc. May, 1921. Paleopsychology. Psychoanalytical Review. Vol. X, No. 2.

MEYER, A. Objective Psychology or Psychobiology. J. A. Med. Ass. Sept. 4, 1925. The Contribution of Psychiatry to the Understanding of Life Problems. Address. What do Histories of Cases of Insanity Teach Us Concerning Preventive Mental Hygiene During the Years of School Life. The Psychological Clinic Press. Philadelphia.Inter-Relations of the Domain of Neuropsychiatry.Archives Neur. and Psychiatry. Aug. 1922.The Philosophy of Occupation Therapy. Arch. of Occup. Therapy, Vol. 1, No. 1.

KEMPF, E. The Autonomic Functions and the Personality.Washington.

WHITE, Wm. A. Outlines of Psychiatry. Washington. Foundations of Psychiatry. Washington.Mechanism of Character Formation. New York. Principles of Mental Hygiene. New York. Insanity and the Criminal Law, New York. The Mental Hygiene of Childhood. Boston. Thoughts of a Psychiatrist on the War and After. New York. The Modern Treatment of Nervous and Mental Diseases (2 Vols.). (With Dr. Jelliffe.) Text-book of Diseases of the Nervous System.(With Dr. Jelliffe.) An Introduction to the Study of the Mind.Washington. Contribution of Modern Psychiatry to General Medicine. Mental Mechanism. Washington. The Behavioristic Attitude. Reprint 101. Nat. Comm. For Mental Hygiene. New York. The New Functional Psychiatry. Archives of Diagnosis, Oct., 1910. Principles Underlying The Classification of Diseases of the Nervous System. J. A. Med. Ass., March 11, 1916.Psychoanalysis and the Practice of Medicine.J. A. Med. Ass. June 2, 1917. Underlying Concepts in Mental Hygiene. Reprint 4 Nat. Comm. for Mental Hygiene. New York. The Meaning of the Mental Hygiene Movement. Publ. No. 17. Massachusetts Soc. for Mental Hygiene. Existing

(37)

Tendencies, Recent Developments and Correlations in the Field of Psychopathology. J. Ner. Men. Dis. July, 1922. The Meaning of "Faith Cures" and other Extra-Professional "Cures" in the Search for Mental Health. A. J. Publ. Health, Vol. 4, No. 3. Psychoanalytic Parallels. Psychoan. Review. April, 1915. Symbolism. Psychoan. Review. Jan., 1916. Individuality and Introversion (as above). Jan., 1916. The Significance for Psychotherapy of Child's Developmental Gradients and the Dynamic Differentiation of the Head Region (as above). Jan., 1917. The Autonomic Functions of the Personality(as above). Jan., 1919.

MISCELLANEOUS.

CANNON, W. B. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage, New York.

CHILD, C. M. Individuality in Organisms. Chicago. Senescence and Rejuvenescence. Chicago. The Origin and Development of the Nervous System. Chicago.

CONKLIN, E. G. Heredity and Environment. Princeton.

D’HERELLE, F. The Bacteriophage. Baltimore.

HERRICK, C. J. Introduction to Neurology. London, Philadelphia.

JENNINGS, H. S. Life and Death, Heredity and Evolution in Unicellular Organisms. Boston. Behavior of the Lower Organisms. New York.

JOHNSTONE, J. The Mechanism of Life. London.

LOEB, J. The Mechanistic Conception of Life. Chicago. Comparative Physiology of the Brain and Comparative Psychology. New York. The Organism as a Whole. New York. Forced Movements, Tropisms, and Animal Conduct.Philadelphia. Proteins and the Theory of Colloidal Behavior.New York.

MORGAN, T. H. The Physical Basis of Heredity. Philadelphia.

McCOLLUM, E. V. The Newer Knowledge of Nutrition. New York.

PATON, S. Education in War and Peace. New York.

ROBACK, A. A. Behaviorism and Psychology. Cambridge.

ROBERTSON, T. B. The Chemical Basis of Growth and Senescence.Philadelphia.

RITTER, W. E. The Unity of the Organism. Boston.

SHERRINGTON, C. S. The Integrative action of the Nervous System.London.

WATSON, J. B. Behaviour. An Introduction to Comparative Psychology. New York.

WHEELER, W. M. Social Life Among The Insects. New York.

CHILD, C. M. Individuality in Organisms. Chicago. Senescence and Rejuvenescence. Chicago. The Origin and Development of the Nervous System. Chicago.

CONKLIN, E. G. Heredity and Environment. Princeton.

D’HERELLE, F. The Bacteriophage. Baltimore.

HERRICK, C. J. Introduction to Neurology. London, Philadelphia.

JENNINGS, H. S. Life and Death, Heredity and Evolution in Unicellular Organisms. Boston. Behavior of the Lower Organisms. New York.

JOHNSTONE, J. The Mechanism of Life. London.

LOEB, J. The Mechanistic Conception of Life. Chicago. Comparative Physiology of the Brain and Comparative Psychology. New York. The Organism as a Whole. New York. Forced Movements, Tropisms, and Animal Conduct.Philadelphia. Proteins and the Theory of Colloidal Behavior.New York.

MORGAN, T. H. The Physical Basis of Heredity. Philadelphia.

McCOLLUM, E. V. The Newer Knowledge of Nutrition. New York.

PATON, S. Education in War and Peace. New York.

ROBACK, A. A. Behaviorism and Psychology. Cambridge.

ROBERTSON, T. B. The Chemical Basis of Growth and Senescence.Philadelphia.

RITTER, W. E. The Unity of the Organism. Boston.

SHERRINGTON, C. S. The Integrative action of the Nervous System.London.

WATSON, J. B. Behaviour. An Introduction to Comparative Psychology. New York.

WHEELER, W. M. Social Life Among The Insects. New York.

HUMAN ENGINEERING